Thomas Gallanis recently posted a working paper asking and answering the question whether racial discrimination can ever be a charitable purpose. You can read the abstract below.

Let’s first consider language because “a rose by any other name” is still a rose. And the Supreme Court decided in Students for Fair Admission that discrimination by any other name — “affirmative action” or diversity, for example — is still discrimination. I should admit, as I have on previous occasions that I have not read SFFA entirely. It’s too painful, whether it’s rightly decided or not. I have relied, instead, on commentator summaries. But I am fairly confident that the Supreme Court equates affirmative action with racial discrimination. Unlike others, I even admit that the logic is inescapable. I don’t try to avoid the issue by modifiers or rough synonyms. I don’t call it diversity, remedial discrimination or even affirmative action. I hate that it was ever made tolerable by the idea of diversity. In hindsight, that seemed only to unshackle affirmative action from its legitimate remedial purpose. Diversity invited many other races, genders and orientations to a slice of the remedial pie. Inevitably, the one race, gender, and orientation excluded ought to have resisted.

I can accept that discrimination in favor of one race necessarily requires discrimination against another. It’s mathematical. But the mathematical certainty doesn’t end the inquiry. The important question is whether racial discrimination can ever be justified by a compelling interest. Gallanis argues that discrimination is intolerable “tout court.” The paper is in its early stage so I cannot say whether he means to imply that affirmative action has always been “odious” for its impact on white people. His conclusion, however tentative it may be, is that “the time has come for state and federal courts and taxing authorities to declare that racial discrimination by a charity violates public policy irrespective of the race of the individuals harmed by it.” That seems to imply his agreement that discrimination of the affirmative action type was, at an unstated prior time, tolerable. Justifiable by a compelling government interest, perhaps.

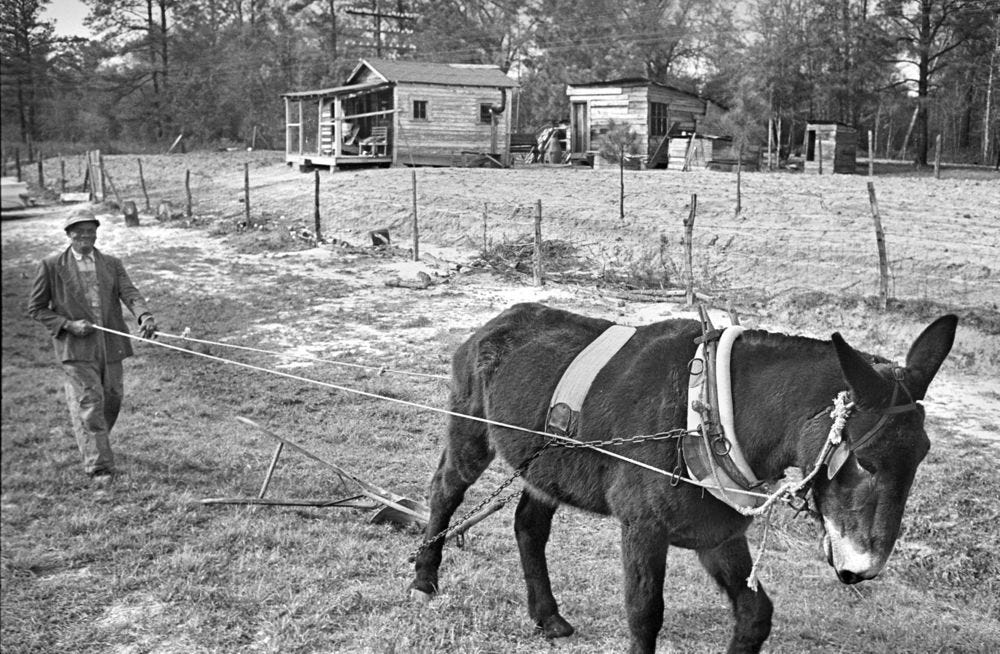

History supports that interpretation. What if, immediately after the end of slavery and the Civil War, the government had lived up to Tecumseh Sherman’s Special Order No. 15, giving newly freed enslaved people 40 acres of land and a mule? From Wikipedia:

Forty acres and a mule refers to a key part of Special Field Orders, No. 15 (series 1865), a wartime order proclaimed by Union general William Tecumseh Sherman on January 16, 1865, during the American Civil War, to allot land to some freed families, in plots of land no larger than 40 acres (16 ha). Sherman later ordered the army to lend mules for the agrarian reform effort. The field orders followed a series of conversations between Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton and Radical Republican abolitionists Charles Sumner and Thaddeus Stevens following disruptions to the institution of slavery provoked by the American Civil War. They provided for the confiscation of 400,000 acres (160,000 ha) of land along the Atlantic coast of South Carolina, Georgia, and Florida and the dividing of it into parcels of not more than 40 acres (16 ha), on which were to be settled approximately 18,000 formerly enslaved families and other black people then living in the area.

Two things. Throughout, Special Field Order No. 15 explicitly includes “negroes” and just as explicitly excludes white people. The land that was to be allotted to newly freed people would have been taken from white people. And even poor white people would not have been eligible for the government benefit. The affirmative action in favor of freed Black people would have necessarily come at the expense of White people. The math is inescapable. But in that day and time, would the discrimination have been odious tout court? I doubt that even the righteously indignant supporters of SFFA would say so. They would have concluded that Sherman’s discrimination was justified by a compelling state interest. People who had been kidnapped, raped, robbed, beaten, branded, and left penniless were suddenly instructed and allowed to go forth and prosper. But with what? How? The whole of white society owed them and thus Sherman’s discrimination was justifiable. I want to think that Gallanis would agree.

The simple point is that whether discrimination is odious tout court or not depends on the recency of history. To the proponents of SFFA, history is not at all recent. In their minds, Black people were unshackled a long time ago. Too long ago for discrimination to be still be justifiable. Gallanis cites statistics purporting to show that even a majority of Black people (56%) agree with SFFA. Personally, I suspect the data is lies and damned lies more than statistics. Opponents of SFFA believe that history is quite recent. They assert that the impact of slavery and its aftermath are still very recent, particularly since freed negroes never actually received 40 acres or a mule.

If proponents think Sherman’s Field Order No. 15, justifiable, it can only be because it was made closely in time to the harm inflicted. To them, it must be that only if history was long ago will discrimination be odious tout court. Thus, discrimination of the sort that might animate a charity to direct its beneficial effect solely to the descendants of enslaved people is intolerable and ought to preclude charitable tax exemption. If history is recent, discrimination as a remedy is not only justifiable and consistent with tax exemption. It is also the only available course of action, except to leave victims without a remedy at all.

So let’s not pretend that the answer is objective. Whether discrimination can be a charitable purpose depends on our view of the recency of history. Here is Gallanis’ abstract. The paper is still in early development. I will be interested to see it in final form.

Is racial discrimination permissible for a charity?

The question is salient and timely. Our nation faces a stark choice between two competing visions of how the law should assess racial discrimination. One view, articulated by Professor Ibram X. Kendi, among others, is that racial discrimination in favor of members of minority groups is an appropriate response to society’s prior discrimination against them. A competing view, articulated by the Supreme Court in SFFA v. Harvard, is that racial discrimination is odious tout court: eliminating racial discrimination means ending all of it.

This Essay tackles an aspect of the question that has not received much scholarly attention. The Supreme Court’s decision in SFFA v. Harvard has prompted commentary on racial discrimination and the Equal Protection Clause of the U.S. Constitution and Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, the latter of which prohibits discrimination by programs and activities receiving federal financial assistance. The commentary also extends to Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which prohibits discrimination in employment, and Section 1981, which prohibits discrimination in, among other things, the making and enforcing of contracts. Recent actions taken by the Trump Administration vis-à-vis Harvard University raise the issue of racial discrimination as a basis for revoking federal tax-exempt status under Section 501(c)(3) of the Internal Revenue Code. But little attention has been given to the law of charity, which derives from the law of charitable trusts. In order to qualify for tax exemption as a charity, a charity must be a charity. What does and should the law of charity say about racial discrimination after SFFA v. Harvard?

This Essay proceeds in four main parts. Part I examines the law of charity and its requirement that a charity must not violate public policy. Part II explores three Supreme Court decisions salient to public policy and racial discrimination. The public policy limitation in the law of charity derives from the law of charitable trusts, but it is influenced by federal law, including the Court’s decisions; also, state law influences federal law when federal courts determine the issue of federal tax-exempt status. Part III examines the legal landscape after the Court’s decision in SFFA v. Harvard. Part IV proposes a path forward, arguing that the time has come for state and federal courts and taxing authorities to declare that racial discrimination by a charity violates public policy irrespective of the race of the individuals harmed by it. A brief conclusion follows.